This is the 7th edition of Inverted Blackness, a photoblog documenting Black immigrants living in America.

STEPHEN: “Growing up here in America, Yorùbá was my first language. That’s the only thing my parents would speak. But when we started going to school, so we wouldn’t get confused, my parents would speak English to us only in English-speaking places. At home, they spoke Yorùbá to us while we responded in English. I couldn’t speak Yorùbá then, although I understood it in a way that my siblings didn’t. Just also because I’ve been interested in Nigerian culture and took it seriously. So, during the pandemic, I met online on Discord a bunch of other Nigerian-American kids who were interested in Nigerian culture. We were all trying to learn Yorùbá, and that’s how we bonded together. I was able to teach myself to speak Yorùbá during the pandemic. Since then, I’ve been a teaching assistant to Professor Alabi at the Yoruba department at Brown University, which is nice. ”

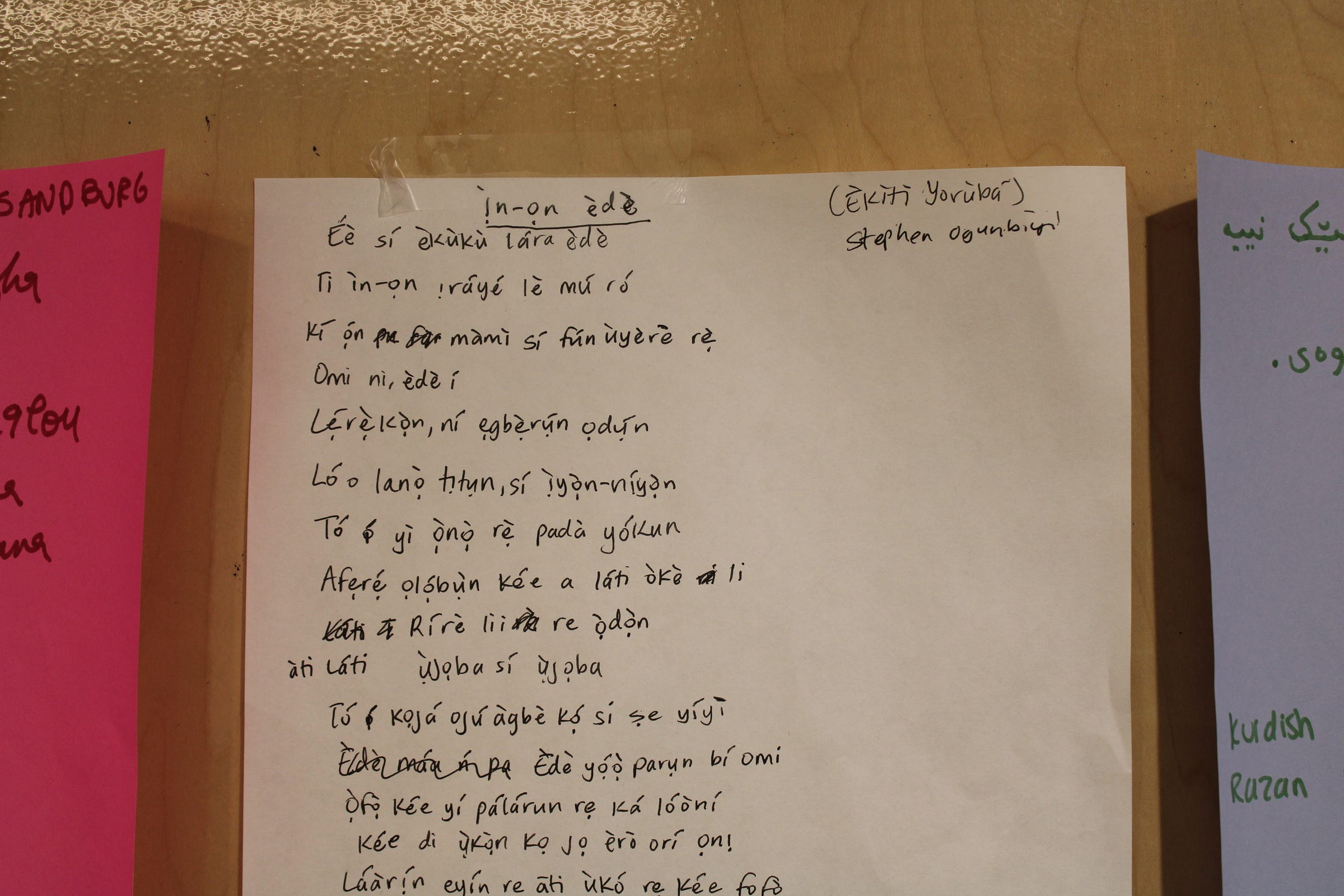

“I know there are just some people who, like, don’t necessarily appreciate their language. They’ve bought into the mentality that just because English is spoken by white people, it’s superior to their native language. They’ve put English on a pedestal. It’s a colonial mindset. I don’t think English is a superior language. People feel like, just because you can’t express some complex terms in Yorùbá, then Yorùbá is inferior. But English is just the same: if you look closely, half of English is made up of borrowed terms from Latin and French. Most immigrant families struggle with stuff like this. Because you have to put in a lot of work in maintaining speaking your native language with your kids if you want them to connect to their roots, especially in the U.S., where they’re supposed to speak English everywhere. I think I’m a very unique exception, and that’s primarily because of my mom’s family. My grandparents couldn’t speak or write English. My mom’s brothers and sisters don’t speak the standard Yorùbá language; they speak the dialect of Ìlara-Mọ̀kin in Ondo State, which is a branch of the Èkìtì dialect. While I was doing my research on my family history and culture, I learnt to speak the dialect. It was important for me to connect to my roots in that way. When I was younger, I suffered a little from fully representing myself as African. I remember that one time in Black History Month when I was asked to wear Nigerian clothing, and I didn’t because I was too embarrassed to do so. I had to give an excuse to go play basketball with my friends to avoid wearing African clothing. I think it goes the same way with how people don’t want to speak their native language anymore.”

“Since I was in high school, it’s made me a little upset, all these opinions regarding your culture. I found it interesting that a lot of people, when they come to the U.S. or go to London, want to assimilate with American and white culture and reject their own traditional culture. A lot of times maybe because they’re Christians who don’t want to engage in their traditional practices anymore, right? But I’ve always thought it interesting because then you have a lot of scholars who are like white, or European, who went to Nigeria and were so fascinated by Yorùbá culture to the extent that they dedicated all their lives to it. People like the Austrian woman, Susanne Wenger—I think her Yoruba name was Àdùnní Olórìshà. I feel like the same pull and interest that made all these Europeans come to Nigeria and witness Yorùbá culture and stay, is the same pull I have towards my culture.”

Stephen Ogunbiyi was born and grew up in the United States. He studies linguistics at Brown University, teaches Yoruba at Brown Center for Language Studies, and is an incoming medical student at the Warren Alpert School of Medicine in Fall 2026.

Thank you for reading Inverted Blackness! This photoblog publishes stories and photographs of Black immigrants living in America, offering a glimpse into the Black diasporic experience in the United States.

If this newsletter is shared with you, kindly consider subscribing and sharing it with others. Please, whitelist the email so you never miss anything from us. Thank you!

Thank you, Stephen for your right thoughts. Feeling your native language is inferior to English is a colonial mindset; no more, no less!

I’ve always aligned with Stephen’s school of thought, which appreciates the Yoruba language and culture and does not consider it inferior to any other.